Upholding humanity, wherever it may be found

23 April 2025

Judy Owen is our longest-serving international delegate. For 40 years, she went into conflict zones with International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to provide humanitarian relief to the victims of war. From Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, she has helped some of the world’s most vulnerable people during their darkest days.

Born and raised in Whanganui, Judy trained as a nurse and was working at Whanganui Hospital when she signed up to be an international delegate in 1979. She was 26 years old when she went on her first assignment and 66 when she finished her final assignment in 2020.

“I did my first mission back in 1980. I went to the Thai/Cambodian border. I knew after the first one that that’s what I wanted to do. I knew that was the direction in my life that I wanted to take.”

Work in conflict zones

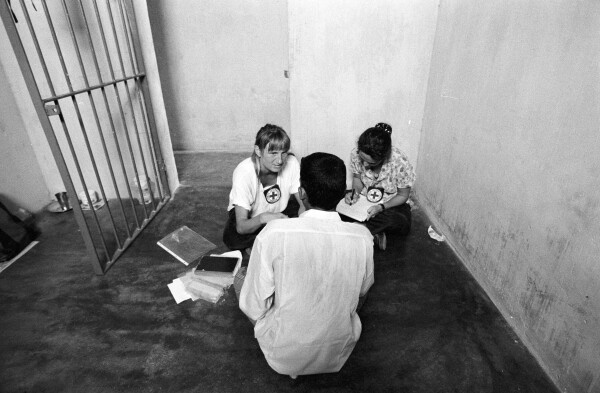

ICRC staff interviewing a person deprived of their liberty in Akkaraipattu prison, Sri Lanka, 1997.

Judy felt that she had the personality, stamina, and knowledge to be a delegate. She was also driven by the desire to help people. “I knew instinctively that I was very capable of doing this work.”

Over 40 years, her work included providing medical care, delivering medical supplies, managing medical centres, visiting people deprived of their liberty, and repatriating people who’d been held in detention or people who were internally displaced. Throughout her work, she upheld humanity in lots of places – in cells, on tarmacs, and in hospitals.

She began doing detention and prison visits in the early 1990s. “Access to these places of detention was controlled by the authorities holding these people. It took time to negotiate access, as ICRC has strict criteria by which it works. Sometimes it took months, sometimes years.”

Once granted access, Judy’s role as a health delegate was twofold – checking the place and condition of detention. Judy first did this type of work in the former Yugoslavia and later visited people deprived of their liberty in Indonesia, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Iraq.

“We’d go in there and look at access to fresh air, access to fresh water, how many people were in the cell, what the food was like, where they got the food from and who cooked it. If somebody got sick, did they have access to healthcare?”

Ethiopian prisoners of war and other people deprived of their liberty waiting to board their repatriation flight in Mogadishu, Somalia, 1988.

The moments Judy remembers most are family reunification and delivering Red Cross Messages to people deprived of their liberty, which she describes as “truly humanitarian”. In 1988, she took part in repatriating Ethiopian prisoners of war from Somalia.

“I remember when the prisoners of war finally saw the plane, and they went up, that was when the excitement got a bit contagious. It was something you couldn’t envision. People being prisoners in another country and all of a sudden, they have got the opportunity to go back home.”

“They walked down the gangplank from the plane and kissed the ground. I found it a very emotional experience as you could feel the emotions of the people in the plane waiting to disembark. When they started to kiss the ground, I was very grateful for my sunglasses.”

Building personal resilience

A child in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1994.

Judy credits her medical training and experience with preparing her for the realities of working in conflict zones. She’d been in situations that were life or death for patients. She’d seen people suffer with illness and injuries and had seen patients die. Through this, she’d built up resilience to be able to cope in high-pressure situations where help was desperately needed, but not always available or going to work.

She also built a mindset that allowed her to give 100% when she was on assignment and be grounded when she was back home. She did this after hearing about a British delegate who struggled to cope once she returned home. The woman couldn’t accept the abundance of everyday items at home after seeing people suffering.

“I knew that if I was going to continue doing this work, I couldn’t afford to be like that every time I came home. I needed to have some sort of protections in place. I made sure that I went out for dinner with friends and that I did lots of normal things, just to keep me grounded.”

Judy at Martini Hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia, 1988.

An Auckland resident since 1981, Judy worked at Auckland or Greenlane Hospitals when she wasn’t on assignment.

“It became a lifestyle for me. I truly believe I had the best of both worlds because I could come and go quite easily. ICRC had 100% of my energy to do a mission and I was able to walk into my job when I got back.”

“Working in conflict areas is a personal decision. You volunteer and do the job – no one is forcing you. However, it’s necessary to acknowledge when it’s time to finish. I always told myself that when I reached a certain age, I wouldn’t accept any more contracts to work in conflict areas.”

A 40-year legacy

Judy in South Sudan, 2014.

Judy is a respected figure within our international Movement and New Zealand Red Cross. She received the Florence Nightingale Medal in 1995, the highest Red Cross award for nurses.

Though Judy retired from working internationally a few years ago, she hasn’t slowed down. When she returned to New Zealand in 2020 she joined the national response to COVID-19 and worked in Managed Isolation and Quarantine. She still works 41 hours a week with a private medical company, though she has plans to go part-time at some stage this year.

An avid history buff and family historian, Judy volunteers each Tuesday at the Auckland War Memorial Museum in the Pou Maumahara Memorial Discovery Centre. Home to the Online Cenotaph, Pou Maumahara is where researchers and relatives can learn about military history.

Volunteering at Pou Maumahara connects Judy to her 40 years of service with Red Cross as well as her own family history. Her father, Dick Owen, served with the Royal New Zealand Navy during the Second World War.

Anzac Day has always been important to Judy, and she’s attended dawn services at the Auckland Cenotaph each year that she’s been in New Zealand.

“I usually go by myself and quietly reflect on memories of my family who have served overseas, but also, I always think of the countries that I've worked in.

“It's a moment of quiet reflection of conflicts where I've personally been involved. I wasn't involved with the First World War, the Second World War, but I have been involved with other conflicts, which have perhaps been under the radar a little bit more. It's a quiet time and I always make a point of going.”

After her decades of seeing the cost of armed conflict up close, Judy has a simple message for people about armed conflict and its impact.

“Conflict with war is about people. It’s not a nice time and has destroyed more lives than have been saved. Attempts must always be made to solve war related conflicts, regardless of how long it takes.”

Header image: A Red Cross flag in NW9 refugee camp, Thailand, 1980.

More information

- In times of disasters, conflict, and other emergencies, we respond to the needs of vulnerable people around the world.

What we do overseas - If you want to get involved in our work, join us! We have volunteer roles to suit everyone.

Find a volunteer role - Donate to support our work, including sending people like Judy overseas to uphold humanity.

Donate to where the need is greatest - Read more about Judy’s work in Aceh, Indonesia after a tsunami struck on Boxing Day 2004.

Judy’s memories of Aceh