“It was just like a war zone” – memories of Aceh

19 December 2024

On Boxing Day 2004, a massive earthquake struck an area off the west coast of northern Sumatra, Indonesia. The 20-metre-high waves reached Aceh in northern Sumatra in minutes, where they smashed into the coast and destroyed everything three kilometres inland. In some areas, the waves reached eight kilometres inland. These scenes were repeated elsewhere, including in Thailand and Sri Lanka.

The world watched in horror as more than 285,000 people were killed and millions more were affected in 14 countries bordering the Indian Ocean.

“It’s very hard to comprehend the tsunami because it affected 14 countries. People just disappeared.”

Kiwi Judy Owen was one of the first international delegates on the ground in Aceh after the Boxing Day Tsunami.

“In Indonesia alone you’re looking at over 100,000 people who disappeared. It’s a lot to take in,” she recalled, 20 years later.

In January 2005, Judy had 25 years of experience as a Red Cross international delegate. A registered nurse since 1974, her service record shows assignments to countless conflict zones across the world. Aceh was familiar in that way. Before being decimated by the tsunami, the region had experienced armed civil conflict for almost 30 years.

“When you have a conflict situation of 30 years, and you don’t have well-functioning services or the service structures aren’t in place, and all of a sudden you have a disaster, it’s very, very difficult for these countries to respond.”

On the ground in Aceh

Aceh from above on 30 December 2004.

Judy was part of the first International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) delegation to arrive in Banda Aceh, the capital of Aceh province, in January 2005.

“I was shocked when I first arrived there. It was absolutely appalling, especially around the coastal area where the tsunami had come in. It was just like a war zone. Everything was just completely taken out.”

Shortly after arriving in Aceh, Judy was shown videos shot by local people after the tsunami made landfall.

“There were people in the city block who managed to get up to the second or third floor, and the water coming in was extremely high. If you were caught up in it there was no way you were going to survive, because you would have been crushed by a car or a building. It was a very, very powerful wall of water.”

Judy and her ICRC colleagues got to work. This included making sure that health centres had enough supplies, that tracing services for missing people were set up, and they established the welfare of people held in detention because of the conflict.

ICRC staff transport a patient in Aceh, December 2004.

Aceh province lost most of its health workers in the tsunami – some died while others had to leave their homes. Many health facilities were also destroyed, including the referral hospital in Banda Aceh.

ICRC supplied first aid kits in communities, set up hospital tents, and provided thousands of medical supplies and pieces of equipment to health centres across Aceh.

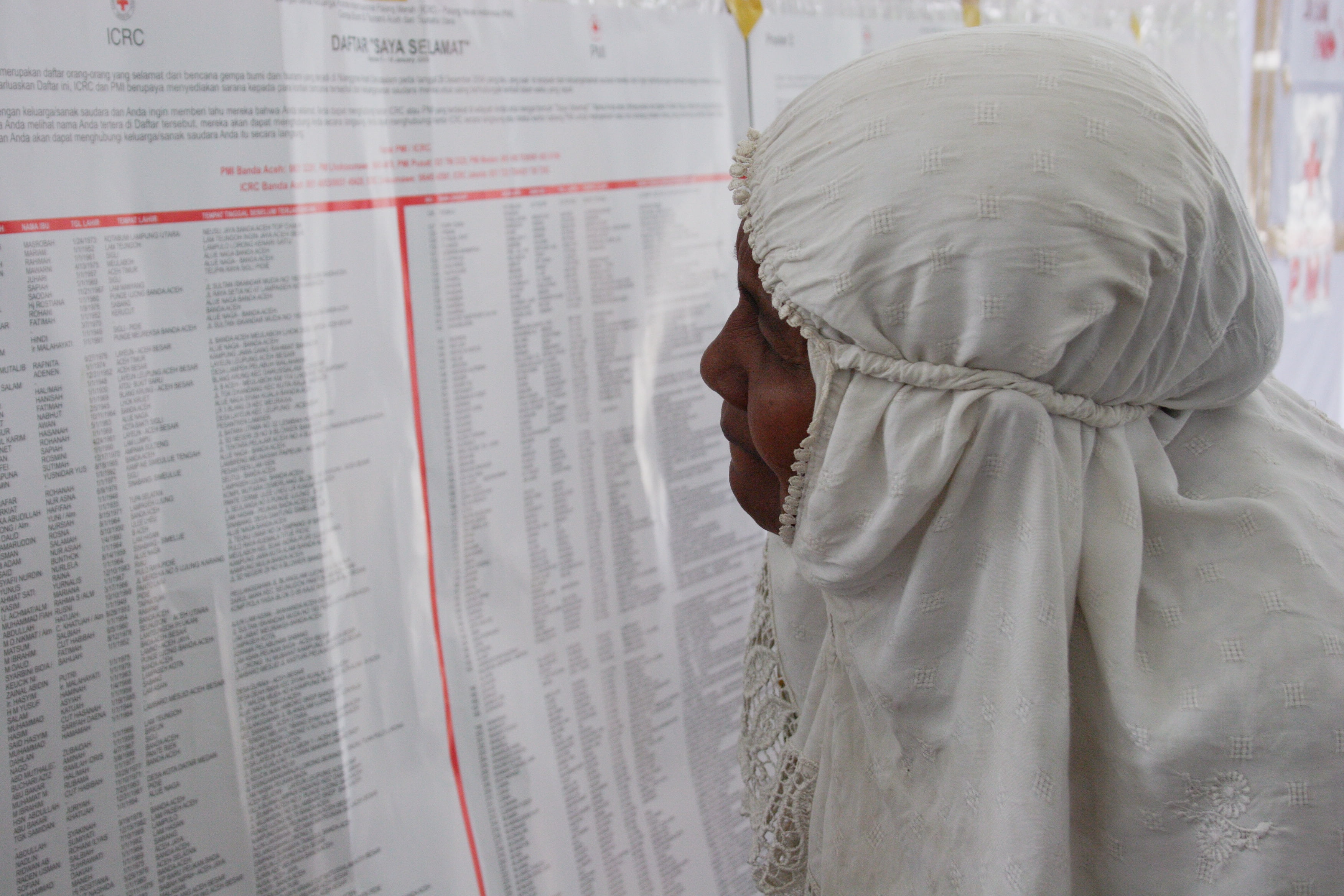

A woman checking the names of registered missing people in Aceh, January 2005.

“There were so many people who were literally swept away and never seen again.”

In Indonesia alone, more than 167,000 people were killed by the tsunami. To this day the remains of many victims have never been found.

A crucial part of ICRC’s work in Aceh was tracing people, which involved registering missing people and doing everything possible to find out what happened to them. Judy especially remembers a man who arrived at the tracing office to register his missing daughter.

“I always remember what he said through a translator, ‘the waves were just so high – they were as high as the palm trees.’ He said that when the first wave came, he could hang on to his daughter, when the second wave came, he struggled to hang on to his daughter, but when the wave came back the third time, he lost his daughter.”

ICRC worked with Palang Merah Indonesia | Indonesian Red Cross to retrieve and bury the remains of more than 126,000 people. They registered more than 37,000 people as missing.

What was then a radical approach to trace missing people was adopted – using the internet. Tracing offices used satellite phones and laptops to constantly update information about missing people. They also used a website where people with an internet connection anywhere in the world could find information about people registered as missing, which had never been done before.

The civil conflict meant that members of the Geurakan Acèh Meurdèka | Free Aceh Movement who were captured ended up detained.

ICRC negotiated with the prison authorities to have access to the detainees. Once the agreement was made, the place of detention and conditions of detention were checked. A date and a time would be set up to go to prisons to do their welfare checks. As a health delegate, it was Judy’s job to check on people’s physical welfare.

“We’d go in there and look at access to fresh air, access to fresh water, how many people were in the cell, what the food was like, where they got the food from and who cooked it. If somebody got sick, did they have access to healthcare?”

In 2005, ICRC visited more than 21,000 people held in 78 detention centres, with 2,000 people individually monitored. Many detainees had family in tsunami-affected areas, so ICRC also activated tracing services and shared Red Cross Messages between families and detainees.

What Aceh looked like when Judy arrived in January 2005.

Though the armed civil conflict in Aceh began in 1976, little was known about it as access to the area was heavily restricted. No press and no outside agencies were given entry to cover the conflict or to provide humanitarian aid.

“No foreigners had been allowed in, no press, no media, so of course when the tsunami happened, they couldn’t manage. When we arrived, we were among the first group of foreigners that had been sent to Aceh in a very long time.”

Working in Aceh had all the elements of working in other conflict zones, including checking in with security agencies and maintaining personal safety. In June 2005 a Red Cross worker was shot but survived.

By August that year, a peace deal was brokered between the Free Aceh Movement and the Indonesian Government. Suddenly people who Judy had been visiting in detention were free and back with their communities.

“I remember driving in one of our land cruisers one day and these two guys passed us on a motorbike. They waved and said hello to us, and they yelled out something to the driver. The driver said to me ‘you just visited this guy a few weeks ago in prison.’ He was a detainee and he’d just been released.”

The legacy of Boxing Day 2004

Indonesian Red Cross volunteers removing human remains in Aceh, January 2005.

After Aceh, Judy continued to work in conflict zones with ICRC for the next 15 years before retiring from international assignments at the beginning of 2020. She remains one of our longest serving delegates, with 40 years of experience helping the victims of war across Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

Recovery from the tsunami was a long process. The first Red Cross search and rescue teams were mobilised in Aceh in December 2004. The last project in the recovery operation — a major infrastructure project that brings piped water to coastal towns in Sri Lanka — was completed five years later. Where there was little or no tsunami warning systems, there are now, so no community should face the potentially catastrophic forces of a tsunami with no warning again.

Many communities are now stronger, more resilient, and better able to face the risks posed by future hazards. Houses can be rebuilt, but scars remain for people who survived and few people alive at that time will ever forget the disaster.

More information

- In times of disasters, conflict, and other emergencies, we respond to the needs of vulnerable people around the world.

What we do overseas - Our skilled delegates are stationed overseas to help save lives, alleviate suffering, and maintain human dignity on the front line.

International Delegate Programme - Find out more about our Fundamental Principles and how they guide our work.

Our Fundamental Principles - Find out more about the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

Our Movement - Donate to support our work, including responding to emergencies, helping former refugees resettle, and delivering meals to people who can’t cook for themselves.

Donate to where the need is greatest